The Afterlife Used to Be Different

To me the question “where’s the evidence that ghosts are real?” sounds trite. I’ve always thought of the existence of ghosts, like the other great metaphysical questions of our time, as something that’s impossible to prove or disprove with science because it’s not something we can measure.

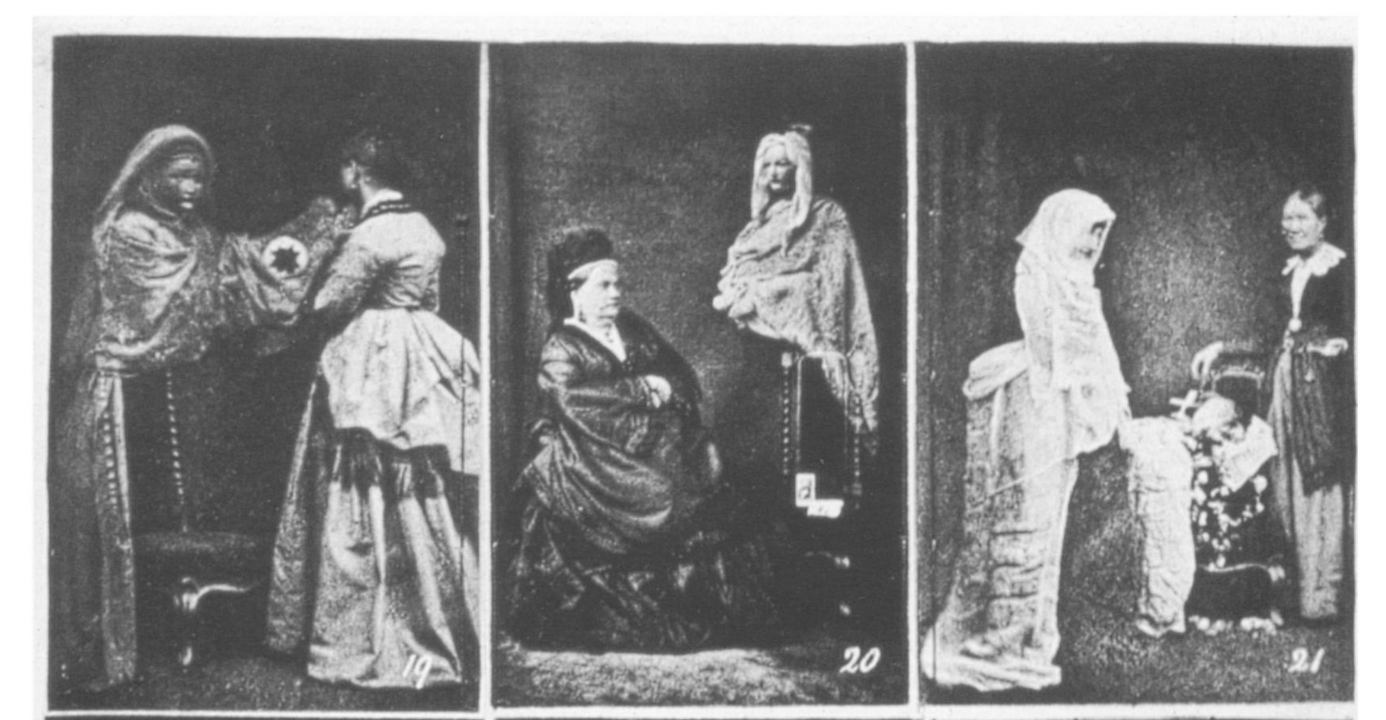

But that’s an idea that came to the United States and United Kingdom only relatively recently. For a long time in the 19th and 20th century, we were surrounded with claims of actual, tangible evidence of ghosts. We communicated with the spirits via mediums. We tried to weigh the soul. We observed ghosts noisily knocking around household furniture. Perhaps my favorite is the concept of spirit photography, where new photograph technology was able for the first time to capture spirits that were invisible to the human eye:

From Karl Schoonover’s “Ectoplasms, Evanescence, and Photography

Spirit photography is a really interesting example of this change, because today we recognize that ubiquituous digital cameras have driven the supernatural nearly to extinction. But in the 19th century, cameras were rare and difficult to use, and it was easy to produce forgeries. Fraudsters produced fake spirit photographs, and many people simply took them at their word.

Cultural and technological changes eventually killed off spirit photography, but the fraud was resilient for much longer than you might expect. Karl Schoonover has a great article titled “Ectoplasms, Evanescence, and Photography” that charts how photography’s relationship with the supernatural changed over time; he writes that spirit photography emerged alongside cameras, but had to evolve as camera technology improved and it became increasingly difficult to produce forged spirit photos. As spirit photographs were increasingly exposed as frauds, they were replaced with ectoplasm:

These bizarre images portray female mediums in varying degrees of displeasure: painfully lactating, vomiting or otherwise leaking stringy webs of white excrement that often contain pictures of faces. Spiritualist investigators alleged that these ectoplasmic excretions – or “teleplasms” – were the material byproducts of spirit activity. In the photographs purporting to document this phenomenon, a violent parable of image production unfolds, as invisible forces wrestle with a human medium, causing a substance from her insides to discharge through her orifices and serve as a conduit for a visual message from the spirit world.

According to Schoonover, as cameras shifted from depicted ghostly spirits to physical ectoplasm, they also shifted from having a supernatural power to depict the spirit world to merely capturing phenomena occuring in the real world. As he puts it, “Photography no longer flaunts its independence from the laws of physics; it simply reveals the truth of the material world in sharper detail.” The “scientists” who studied the phenomena built elaborate setups and tried to convince viewers that state-of-the-art camera technology was the only thing able to capture ectoplasm emissions that appeared for mere seconds and were destroyed by exposure to bright light. The evidence of the spiritual evolved to meet the demands of a public that is increasingly literate with photography and science, and ectoplasm survived well into the first half of the 20th century.

Not everyone believed in mediums, or ectoplasm, or spirit photography, of course, and you can find depictions of ghost skepticism in writing that feels very modern. The protagonist in the 1856 ghost story “The Last House in C– Street” opens with a remark that reads as extremely familiar to a 21st century ghost skeptic:

I am not a believer in ghosts in general; I see no good in them. They come – that is, are reported to come – so irrelevantly, purposelessly – so ridiculously, in short–that one’s common sense as regards this world, one’s supernatural sense of the other, are alike revolted. Then nine out of ten ‘capital ghost stories’ are so easily accounted for; and in the tenth, when all natural explanation fails, one who has discovered the extraordinary difficulty there is in all society in getting hold of that very slippery article called a fact, is strongly inclined to shake a dubious head, ejaculating, ‘Evidence! it is all a question of evidence!’

This is of course a ghost story where the protagonist is proven wrong, but it’s presented as a plausible viewpoint for a reason.

But when you look more into 19th and 20th century ghost skepticism, what you find is people engaging with serious claims about what ghosts are capable of, in a way that no one does these days. James Black writing in Scientific American in 1922 about “Ectoplasm and Ectoplasm Fakers” described the debunking of a wide range of ectoplasm forgeries; I like the story of the medium who was searched and covered with a mesh net, after which she was unable to produce any substantial results. But beyond being funny, the claims are specific and material in ways that you never see today: mediums claim that they can produce ghastly imagery and physical ectoplasm, and that they can do it reliable enough to reproduce in a laboratory setting. The article mentions multiple scientists (including Sir Arthur Conan Doyle) who claim to be able to describe the specific chemical compositions of ectoplasm!

What happened between now and then? Well, people observed and studied this stuff. They followed James Black’s example and looked critically at the evidence, and published their results. Some of this work is still ongoing; mediums who produce readings based on photos of deceased loved ones are particularly difficult to study and you can find relatively recent research from pyschologists on the issue. But it’s clear looking at these historical debates about ghostly phenomena that the realm of possibility has shrunk massively from it’s heyday one hundred years ago.

I’m personally left wondering: do Americans actually still believe in ghosts? Our believes about the supernatural have shifted over time, and incorporated the belief systems of people from countries that never believed in spirit photography or ectoplasm, but much of our ghost imagery and cultural lore around ghosts is still inherited directly from a time when people had beliefs that we now see as disproven. The modern American ghost looks and sounds very much like a 1920 ghost, but without ever manifesting in ways people can observe. In a lot of ways it feels itself like the ghost of the spectral phenomena that came before it, a sort of sad afterlife for an idea that used to hold a lot of power.

End notes

- When I talk about ghosts here, I’m thinking of a particular kind of spiritual phenomena that mostly originates in the US and UK. This isn’t intended as a commentary on how other cultures think about the afterlife or the spiritual. I’ve added some post-publish edits to emphasize this a little better.

- The book that got me thinking about this was Mary Roach’s Spook, which is a great read about the relationship between science and the supernatural.